White Armband

1. White Armband, Oil on canvas. 60 x 60cm. 2019.

A woman clutches her two children and a smashed photograph of a once happy family. Her husband is being ‘questioned’ in the notorious Omarska concentration camp where, during 1992, hundreds of men and women suffered extreme sexual abuse, were tortured and a large number murdered. Their bodies were then dumped in mass graves.

The Muslims and non-Serbs of Prijedor had been ordered on the 31st May 1992 to hang white sheets from the windows of their homes and wear white armbands in order to be easily identified. They were then forced to sign a document stating they would never return, before being

‘ethnically cleansed’ by the Bosnian Serb army.

This painting was inspired by my friend Elvira Mujkanović from Prijedor, who was reunited with her then-boyfriend, Jasmin, in a refugee camp in Croatia before marrying and arriving in Scotland, where she and her family now live. Between them, they survived four concentration camps.

Welcome to Hell

2. Welcome to Hell, Oil on canvas. 100 x 80cm. 2020.

Up to two million people were ethnically cleansed during the Bosnian conflict, mostly Muslims. Many searched in vain to find a place of safety and became refugees or were internally displaced.

This painting symbolises the many women who struggled to feed, clothe or find a place of safety for their children, and lived in constant fear for their lives. The absence of men in the image shows that many men had already been killed or taken to concentration camps.

On the bullet-pocked wall, images of Ratko Mladić, former Bosnian Serb Army General, and Radovan Karadžić, former President of Republika Srpska, are featured. These are the highest-ranking war criminals to be convicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina and orchestrators of the genocide in Srebrenica. Obscene graffiti is daubed on the wall by a Dutch UN ‘peacekeeping’ soldier describing Muslim women. A Muslim has replied by writing: “UN - United Nothing.”

In this painting, I’ve tried to illustrate the despair felt by many innocent women and children who found themselves victims of the campaign of genocide and warfare.

Women of Srebrenica

3. Women of Srebrenica, Oil on canvas. 90 x 80cm. 2018.

On 11th July 1995, the women, children and elderly, after enduring a three year long siege, were forcibly deported from the so-called ‘UN Safe Area’ of Srebrenica. Many suffered rape, starvation, humiliation, and were robbed of their possessions. They had to walk, or be bussed the 40 kilometres to Tuzla, the nearest ‘Safe Area’. Many, including children, were beaten or killed by Serbs on the road.

Ratko Mladić, the Bosnian Serb Commander, told the women that their men would join them soon after being questioned. The women waited, but of the thousands of men, only a few arrived in Tuzla. The rest were executed and buried in mass graves. The official figure for those killed in the Srebrenica genocide is 8,372.

I was inspired to do this painting by the dignity shown by ‘The Mothers of Srebrenica’ who came to our temporary mortuaries to identify the clothing of their missing men.

Men of Srebrenica

4. Men of Srebrenica, Blinded by the Light, Oil on canvas. 100 x 80cm. 2019.

During the Srebrenica genocide, thousands of men and boys from Srebrenica ran into the forest to escape certain death by the Bosnian Serb Army. They faced shelling, machine gunfire and minefields. They saw Bosnian Serb soldiers, who had disguised themselves by wearing Dutch UN uniforms, calling to them to surrender and, believing they would be safe, many gave themselves up, only to be taken immediately to the killing fields and executed. Their bodies then thrown into mass graves.

This painting was inspired by Hasan Hasanović and Nedžad Avdić two of the few who survived the ‘death march’ to Tuzla.

Grave Faces

5. Grave Faces, Oil on canvas. 60 x 60cm. 2019.

The women came to the temporary mortuaries to look at the clothing laid out on the floor. These clothes had been removed by the forensic technicians from the bodies of the victims which had been exhumed from the mass graves around Srebrenica. The women knew that if they recognised an article of clothing, their men would be dead, despite being told by Mladić that they had been taken only for questioning. The women were able to identify clothing with a degree of certainty due to the darning and stitching work on the items of clothing, though some misidentifications were inevitable until the development of DNA testing.

At first, there was silence as they walked around, examining every article of clothing, then gradually there came the inevitable outpouring of grief that built up to a crescendo of uncontrolled wailing that pierced the souls of everyone in the room like a knife.

This painting was inspired by ‘The Mothers of Srebrenica’ who suffered and still suffer from their loss, whose faces I will never forget.

Grave Embrace

6. Grave Embrace, Oil on canvas. 40 x 30cm. 2020.

Torn rags of clothing, rifle bullet shell casings, personal belongings, scattered and broken bones, the remains of innocent men women and children, together with the stomach-churning odour of death, make up the scenes of carnage in the mass graves.

The forensic experts carefully removed them from this hell, cleaned and put them together again, identified the bodies and returned them to their families to allow some form of dignity in death, and giving them the opportunity to grieve.

This painting is in recognition of those experts, and in memory of those who died needlessly.

The Body Factory

7. The Body Factory, Oil on canvas. 60 x 50cm. 2020.

In the spring of 1996, the first international team of forensic specialists arrived in Tuzla to begin the exhumations of mass graves and examine the bodies of victims found in them on behalf of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

A bombed-out garment factory was used as a temporary mortuary. Conditions in this place were challenging, and security quickly became an issue when threats of disruption to our work became apparent.

The painting features a technician searching a body for bullets, a photographer, and a detective.

Nedžad Avdić

8. Nedžad Avdić , Oil on canvas. 80 x 80cm. 2016.

On July 11th 1995, Nedžad was taken, hands tied behind his back in a truck along with other Muslim men to one of the killing fields near Srebrenica. Three bullets tore into his body as Bosnian Serb executioners shot him. The dead bodies of his uncle and cousin were then thrown on top of him. His pain was so intense he prayed for death, but somehow he managed to crawl from the grave where he met another survivor and eventually made his way to safety through the danger-filled forest to Tuzla.

This painting depicts three stages of his horrendous experience:

•As he lay in the grave alive.

•As he remained silent for 20 years, in fear for his family’s safety.

•As he is today.

In the background are ‘missing' friends and relatives.

The snuffed out candle represents sudden death.

Nedžad returned to Srebrenica, now a Bosnian Serb dominated town, where he lives today.

In 2017 Nedžad received an Honorary Doctorate of Philosophy from the University of Bedfordshire.

I’ve been privileged to hear him share his testimony on numerous occasions.

Lens Flare

9. Lens Flare, Oil on canvas. 60 x 60cm. 2019.

The subject of this painting was inspired by the death of journalist and war correspondent Marie Colvin who was killed while covering the siege of Homs, Syria in February 2012. I transferred the background to the siege of Sarajevo, as I believed there were strong parallels between the conflict in Syria and the Bosnian War.

In this painting, I wanted to demonstrate not only the needless killing of the innocent but also represent the dangers facing those who record and report from such war zones.

The title refers to the blood-spattered camera lens of the photographer. In the background is the newspaper building Oslobođenje, where despite being shelled every day by Bosnian Serb snipers, cannons, mortar, and tanks, journalists managed to produce a daily news-sheet.

Three Flowers for Sarajevo

10. Three Flowers for Sarajevo, Oil on canvas. 120 x 90cm. 2016.

1. ’The Sarajevo Rose’. After the four-year-long siege of Sarajevo, when the Bosnian Serb mortar shells exploded in the streets and people were killed or injured, students filled the shell bursts with red enamel resin as a memorial to them. It is regarded as unlucky to walk on them.

2. The ‘Srebrenica flower’ is worn by Rešad Trbonja, who as a 19-year-old was given a rifle and asked to defend the city against the Bosnian Serb army surrounding the city. As well as fighting on the front line, he often crawled through the narrow, often flooded, tunnel under the city, to forage food for his family and others.

3. The iris represents the flower of hope for the future.

This painting is dedicated to Rešad, whom I’m proud to call a friend. In 2018, Rešad was made an Honorary Associate Professor by De Montfort University’s Criminal Justice Division.

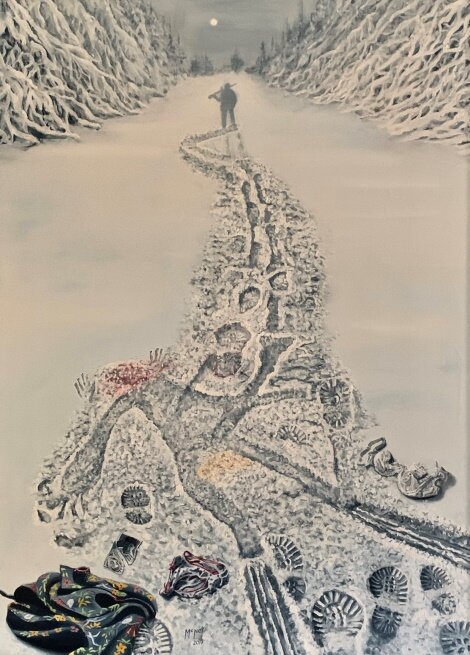

The Persistence of Memory

11. The Persistence of Memory, Oil on canvas. 60 x80cm. 2017.

It is estimated that up to 50,000, mainly Muslim women, suffered extreme sexual violence during the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Many of the women were systematically and repeatedly raped by Bosnian Serb soldiers and paramilitaries. It was used as a cheap, but effective and devastating weapon of war. They were then forced to carry their babies to full-term “to dilute their Muslim blood.”

This painting highlights the silence surrounding these violent crimes that soldiers felt they could commit with impunity. The snow, and therefore the evidence will soon be gone, but not the night-terrors and mental health issues that may never fade for the victims. The tangled forest represents escape was impossible.

Bakira Hasečić’s story inspired me to paint this picture. In 1992, the local police chief, along with Bosnian Serb soldiers entered her home. They placed the family under house arrest, repeatedly raped Bakira and her eldest daughter and robbed them of their savings. The soldiers then slashed her daughter’s face and they were left for dead.

Bakira, despite constant threats, has dedicated her life to the Association of Women Victims of War to help bring the perpetrators of war-rape in Bosnia and Herzegovina to justice and to support other victims.

Her attackers have never been arrested.

She now lives in Sarajevo.

In 2018 Bakira received an Honorary Degree of Doctor of Laws from Glasgow Caledonian University.

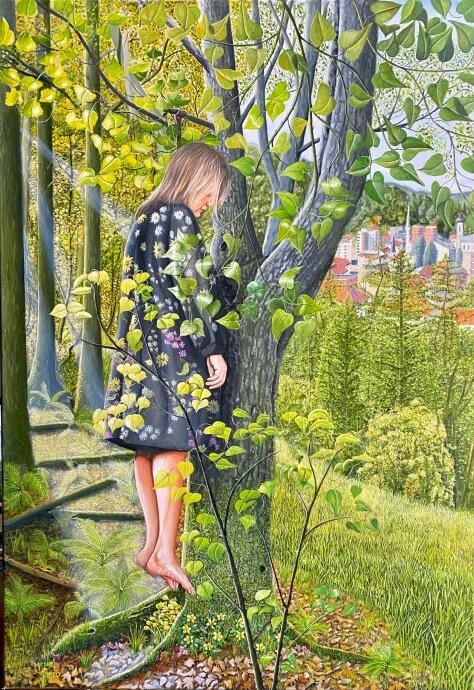

Betrayal

12. Betrayal, Oil on canvas. 70 x 100cm. 2020.

Many Muslim women raped in Bosnia and Herzegovina by Bosnian Serbs, took their own lives rather than facing face the shame of the stigma attached to rape, the cheapest weapon of war. Actual figures can only be guessed at, but it’s estimated that up to 50,000 women suffered.

I dedicate this painting to the women who felt that the only way to eradicate the memory of their suffering was to destroy themselves.

My inspiration for this painting came after seeing a very moving photograph, taken by Darko Bandić in 1995 of a woman called Ferida, soon after she was found dead and hanging from a tree in the forest near Tuzla. After enduring a siege involving starvation and deprivation that lasted for almost four years, Ferida was forcibly deported from the so-called ‘UN Safe Area’ of Srebrenica to Tuzla, 40 kilometres away. Many of the women were raped and abused by soldiers en-route to Tuzla.

Ferida waited for her husband to arrive after being taken for ‘questioning’ by the Serbs.

Her husband never arrived in Tuzla, and his body most likely lies in an undiscovered mass grave. Only a handful of the eight thousand men from Srebrenica managed to escape. The others were captured, executed and thrown into mass graves. Ferida’s two children are still alive.

I first noticed the photograph of Ferida at the Potocari Memorial (Srebrenica) in 2015. I felt deeply saddened by it.

Srebrenica is the town depicted in the background of the painting.

Remembering Srebrenica

13. Remembering Srebrenica, Oil on canvas. 50 x 70cm. 2020

On 11th July 1995 and over the following four days, over 8,000 Muslim men and boys from Srebrenica were beaten and then systematically executed by Bosnian Serb soldiers, and thrown into mass graves. In total, over 100,000 people died in Bosnia and Herzegovina, predominantly Muslims.

To date, over 6 thousand bodies have been recovered and identified. They are now re-buried respectfully in the Srebrenica-Potočari Memorial Centre and Cemetery beside the former Dutch Battalion HQ, whose soldiers the Bosnian Muslims believed were there to protect them, but didn’t.

To this day bodies and body parts are still being discovered in and around Bosnia and Herzegovina. Many believe that had they acted more decisively, the politicians in the West could have prevented this atrocity.

2020 represents the 25th anniversary of this atrocity, the only genocide to have happened in Europe since the Holocaust. The smoke from the snuffed-out candle symbolises their sudden deaths. The candle sits on a Muslim prayer mat. A Celtic knot on the mat symbolises the support for Bosnians who escaped to Scotland.

Self Portrait

14. Self Portrait, Oil on canvas. 60 x 60cm. 2019.

The final image, end of the presentation.

Other related works by Robert McNeil and other work can be seen here.